By Pablo Ortuno

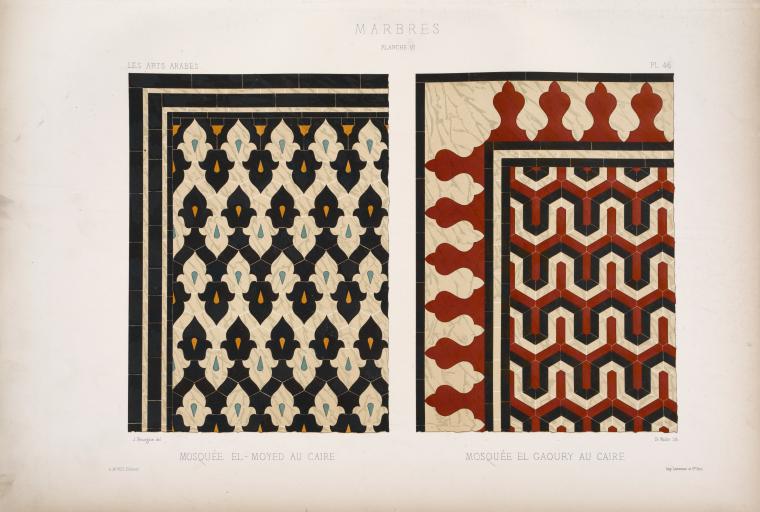

Cover image: Marble in El-Choury Mosque, Cairo. (Bourgoin, 1873)

“Create the object, mould it from your culture, your art, religion, philosophy, and future. Mathematics will reveal themselves if they’re there.”

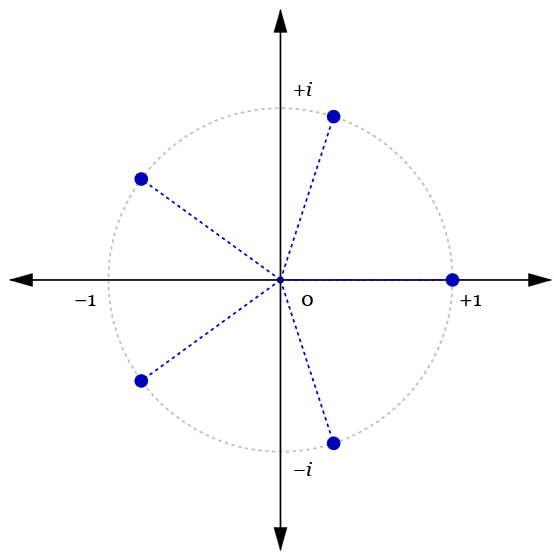

In 1832, French mathematician and revolutionary Evariste Galois dies aged twenty in a fated duel in the middle of a lover’s quarrel, leaving behind in a letter the grounds for a solution to a problem which had stumbled mathematicians for hundreds of years. Galois’ solution studied symmetry in an abstract context, exemplified in Figure 1.

His ideas were picked up later by Camille Jordan (1838-1922), who formalised symmetry in mathematical terms by coining the structures known as “groups”. His work revolutionised the field of algebra at the time, storming the academic elites in Europe into a considerable development in mathematics. Nowadays, group theory, the study of symmetry, is an essential part of mathematics curriculums across universities worldwide.

Nevertheless, the study of symmetry hasn’t always been from a mathematical perspective. One of the largest cultural expressions of symmetry we have evidence of is that of Islamic geometric patterns, particularly those tessellations of a plane with infinitely repeating geometric constructions.

This decorative style highly concerned with symmetry stems from religious beliefs on the omittance of human and animal representations, and philosophies on the infinity of God and the nature of His creation. The art and the craft needed to be transcendental, formless, and precisely constructed. Words which echo how we think (and thought, back in the days of Jordan and Galois) of pure mathematics being abstract and axiomatic.

It is then perhaps not surprising that we think of these highly geometrical wallpapers as being mathematical in nature. In doing so, however, we obfuscate the material aspect, the creative exercise, and the artisanal process behind the creation of such ornaments. The symmetry group found in a wooden window in a funerary complex in 1500’s Delhi may be the same as the one plastered in a shop in 1300’s Cairo, but the pieces are anachronical, extraneous, and made of different materials. These differences can all be forgotten in lieu of the ornaments being mathematical.

However, looking at these ornaments from a mathematical point of view, analysing the symmetry they present, is a fruitful exercise. In doing so, we have gained insight into complex mathematical structures, and the activity of “hunting for groups” presents a lot of didactic opportunities: It allows us to approach abstract mathematics from a familiar place which does not require much prior knowledge and feels intuitive. We see then an opportunity to flip the script in how abstract mathematics is often taught. By putting forward intuition-based methods in the teaching of mathematics, which we bring to life in this workshop, we take the artisan’s point of view and produce infinitely tessellating ornaments through stamping. Placing the process before the abstract, renouncing the mathematical appropriation of our ornaments.

Our workshop is precisely a testament to a cultural construction of mathematics: Create the object, mould it from your culture, your art, religion, philosophy, and future. Mathematics will reveal themselves if they’re there.

‘Recreating Islamic Geometry’ will be held on 13/09/2025 from 2-4:30pm, in collaboration with Words and Actions for Piece at 58 Ratcliffe Terrace, EH9 1ST.